Introduction: The Fracturing of Global Tech

The era of borderless technology is ending. What began as targeted export controls on cutting-edge semiconductors has evolved into comprehensive digital sovereignty regimes that will fundamentally restructure how technology companies compete globally.

This transformation is not driven by ideology but by strategic necessity. When AI capabilities determine economic competitiveness and military advantage, no major power can afford to remain dependent on rivals for critical inputs. The result is an accelerating fragmentation of global tech platforms along geopolitical lines.

This analysis is part of our Modern Mercantilism research series, examining how state-driven economics is reshaping global markets.

Key Takeaways

- 80% probability of US GPU export caps: By 2028, AI chip exports to China will likely be capped at 10% of 2023 levels, reshaping the $100 billion+ AI hardware market

- ASEAN AI licensing regimes: Nations like Indonesia and Vietnam will require local registration for foreign LLM APIs, fragmenting the large language model market along national lines

- UK sovereign compute mandates: By 2029, the UK will likely require sovereign-compute certificates for AI deployment in critical infrastructure

- China IoT exclusion: Proprietary IoT security standards will effectively bar Western tech firms from China's $100 billion+ connected device market

- Taiwan fab investment restrictions: Investment in sub-3nm semiconductor fabs will be barred to companies from unfriendly nations

- Technology bloc formation: Global tech markets will split into distinct Western and Chinese stacks with limited interoperability

The Logic of Tech Sovereignty

Technology sovereignty emerges from a simple strategic calculation: dependence on foreign technology creates vulnerability. When the US demonstrated it could cripple Huawei through chip export controls, every major economy drew the same conclusion. Technological self-sufficiency became a national security imperative.

The dynamics compound quickly. Export controls on finished chips lead to controls on chip-making equipment. Controls on equipment lead to controls on the materials used to make equipment. Each restriction expands the scope of the next. The world is bifurcating into competing technology blocs: one centered on US-allied supply chains, another on Chinese domestic alternatives. Companies caught in the middle face an impossible choice: pick a side or lose access to both.

For investors, the implication is profound. Technology companies can no longer be evaluated purely on product merit or market position. Their geographic exposure, supply chain dependencies, and alignment with state priorities now determine competitive viability. A company with the best product but wrong geopolitical positioning will lose to a competitor with inferior technology but superior political alignment.

Forecast 1: US GPU Export Caps

80% probability: By 2028, the US will impose a quota capping annual AI-training GPU exports to China at 10% of 2023 levels (trackable via Commerce license data).

Washington has already banned advanced GPUs to China and set country-specific shipment caps. A hard 10%-of-baseline quota becomes the next enforcement lever, reshaping the $100 billion+ AI hardware market.

The Mechanism

The current export control regime relies on performance thresholds that chip designers can sometimes engineer around. A quota-based system eliminates this loophole by capping total shipments regardless of specifications.

Commerce Department license data already tracks shipments by destination. Converting this tracking into hard caps requires only regulatory adjustment, not new infrastructure. The 10% threshold allows continued civilian and academic use while throttling military and AI-training applications.

Investment Implications

The GPU export cap scenario creates a bifurcated market with distinct winners on each side. Domestic Chinese chip designers, particularly SMIC and Huawei's HiSilicon division, gain protected market share as the only viable option for Chinese AI development. Their technology may lag Western alternatives, but captive demand ensures profitability. Non-Chinese AI chip alternatives from AMD and Intel capture diverted demand from customers who previously defaulted to NVIDIA but now need supply chain certainty. AI infrastructure providers in allied nations benefit from accelerated investment as Chinese alternatives become inaccessible.

The challenged players face existential questions about their business models. NVIDIA faces $10 billion or more in annual revenue at risk from China exposure, a significant portion of its AI chip business. Chinese AI labs face 2-3 year development delays per industry estimates as they retrain workflows for domestic hardware. Global cloud providers with China-dependent capacity must restructure operations to serve clients increasingly concerned about geopolitical exposure.

Timeline Catalysts

The path to hard export caps follows a predictable escalation pattern. During 2025-2026, expect progressive tightening of current controls and systematic closure of the engineering loopholes that chip designers have used to skirt performance thresholds. By 2027, Congressional pressure for harder caps will intensify following demonstrations of Chinese AI capabilities that close the gap with Western systems. The formal quota regime will likely arrive in 2028 through Commerce Department rulemaking, implementing the hard caps that earlier measures merely approximated.

Forecast 2: ASEAN AI Licensing Regimes

70% probability: Between 2026-2029, an ASEAN country like Indonesia or Vietnam will publish an AI licensing regime banning foreign large-language model APIs that are not locally registered.

Indonesia's digital strategy explicitly seeks adoption of Indonesia-based AI models. Data-territory rules will translate into API restrictions requiring government registration, effectively barring unvetted foreign AI platforms.

The Mechanism

Indonesia has already signaled this direction. Its National AI Strategy prioritizes domestic AI development. Data localization requirements for financial services and government applications create the regulatory infrastructure for broader AI restrictions.

The registration requirement serves multiple purposes: ensuring compliance with local content laws, enabling government monitoring of AI outputs, and creating market share for domestic alternatives. Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia face similar incentives.

Investment Implications

ASEAN AI licensing creates opportunities for players with local positioning. Local AI startups with established government relationships gain protected market share, as their domestic status qualifies them for licenses that foreign competitors cannot obtain. Regional cloud providers offering compliant infrastructure become essential partners for any company seeking to deploy AI in these markets. Consulting firms specializing in regulatory compliance find a lucrative new practice area helping multinationals navigate the emerging requirements.

The challenged players face a fragmented market that undermines their scale advantages. US hyperscalers (Google, Microsoft, and Amazon) face market access restrictions in regions where they previously competed freely on service quality. OpenAI, Anthropic, and other API-first AI companies discover that their business model assumes cross-border data flows that these regulations specifically prohibit. Multinational corporations dependent on global AI deployments must either accept reduced capability in ASEAN markets or invest in market-specific infrastructure that eliminates economies of scale.

The Fragmentation Pattern

This forecast exemplifies how tech sovereignty cascades through regional markets. When one major ASEAN economy implements AI licensing, it creates immediate pressure for neighbors to follow, both to capture the same economic benefits and to avoid becoming the path of least resistance for unregulated AI deployment. By 2030, operating a unified AI platform across Southeast Asia may require separate regulatory approvals, local data centers, and modified models for each jurisdiction. The administrative burden alone creates barriers to entry that favor established regional players.

Forecast 3: China IoT Security Standards

70% probability: By 2026, China will mandate that all IoT devices sold domestically use the proprietary China IoT Security Standard, effectively excluding Western tech firms from a $100B+ market (per MIIT regulation).

China already requires local encryption standards for various technologies. Extending this to IoT creates a massive non-tariff barrier while claiming cybersecurity necessity. This forces companies to choose: comply and share IP, or lose market access.

The Strategic Logic

IoT devices collect vast amounts of data from homes, factories, and critical infrastructure. From Beijing's perspective, allowing foreign-controlled devices to operate within China creates unacceptable surveillance and sabotage vulnerabilities. Every connected sensor, camera, and controller represents a potential entry point for foreign intelligence services or a node that could be weaponized during conflict.

The security standard requirement achieves multiple strategic objectives simultaneously. It excludes Western competitors without the diplomatic friction of explicit trade barriers, framing market protection as legitimate cybersecurity. It forces technology transfer from companies that value market access enough to share intellectual property in exchange. It accelerates domestic IoT ecosystem development by guaranteeing market share for compliant Chinese firms. And it creates export opportunities for Chinese-standard devices in Belt and Road markets that accept Chinese technical specifications.

Investment Implications

The IoT security standard creates a protected domestic market for Chinese technology champions. Xiaomi, Huawei, and Tuya gain guaranteed access to a $100 billion+ market from which competitors are effectively excluded. Domestic semiconductor suppliers for IoT applications benefit from the requirement to use Chinese chips in compliant devices. Chinese cloud platforms providing IoT backends become the only viable option for connected device manufacturers serving the domestic market.

Western technology firms face a stark choice with no good options. Smart home and industrial IoT providers from Western countries must either invest heavily in China-specific product lines (likely sharing technology in the process) or accept exclusion from one of the world's largest and fastest-growing markets. Apple, with significant China revenue exposure, faces particular pressure as its ecosystem-centric model conflicts with Chinese sovereignty requirements. Qualcomm and other Western chipmakers serving IoT markets lose design wins as Chinese manufacturers shift to domestic semiconductors.

The $100B Market

China's IoT market exceeds $100 billion annually and is growing at 15% or more per year. The scale of this market fundamentally changes competitive economics for global IoT development. Western firms excluded from China lose the volume that would amortize R&D costs and fund next-generation development. Chinese firms gain captive demand that funds aggressive expansion into global markets. The asymmetry compounds over time, and each year of exclusion widens the gap between firms building scale in China and those locked out.

Forecast 4: Taiwan Fab Investment Restrictions

60% probability: By 2027, Taiwan will bar investment in any new sub-3nm semiconductor fabs to companies from unfriendly countries (enacted through an MOEA Ministry of Economic Affairs regulation).

Taiwan has already tightened chip tech transfer to China. A recent amendment explicitly lets Taiwan's Ministry of Economic Affairs reject overseas investment deals that threaten national security. With PLA pressure rising, Taipei is likely to mark cutting-edge fabs as critical, reserving them only for trusted allies.

The Geopolitical Context

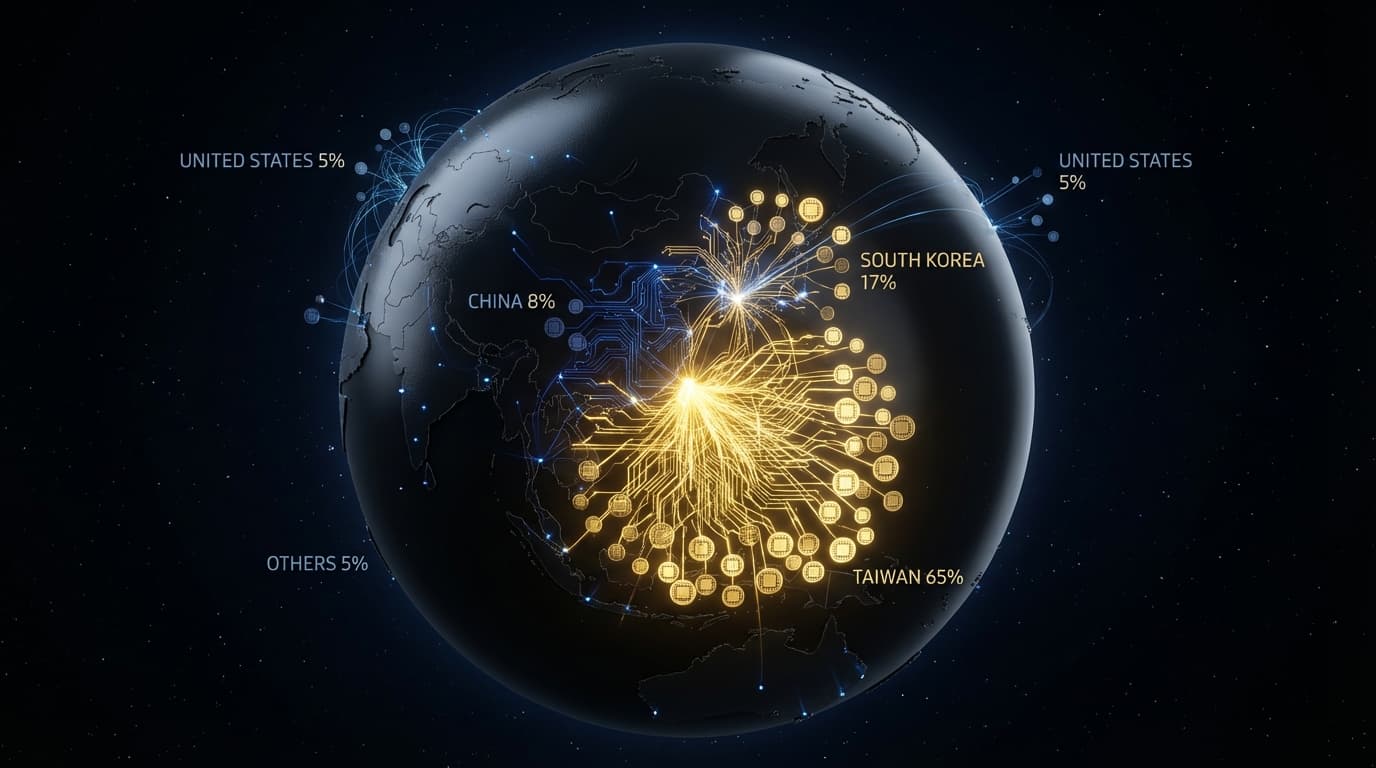

Taiwan produces over 90% of the world's most advanced semiconductors. This concentration creates both leverage and vulnerability. As cross-strait tensions rise, Taiwan faces pressure to ensure its most valuable technology serves allied interests.

The distinction between friendly and unfriendly nations maps directly onto security relationships. Countries with defense commitments to Taiwan (US, Japan, potentially others) gain preferential access. Countries aligned with China face exclusion.

Investment Implications

Taiwan's investment restrictions reshape competitive dynamics in advanced semiconductors. TSMC benefits from both protected domestic position and preferential access to allied markets, cementing its status as the indispensable foundry for the Western technology ecosystem. Samsung gains importance as an alternative source for allied nations seeking supply chain diversification, even though its technology trails TSMC. US and Japanese semiconductor equipment makers benefit from the concentration of advanced fab investment in allied nations, as their equipment qualifies for use in security-sensitive facilities while Chinese alternatives face exclusion.

The challenged players face fundamental business model questions. Chinese chip designers dependent on Taiwan foundries (which includes most of China's cutting-edge semiconductor companies) lose access to the production capacity they need for advanced nodes. European chipmakers without clear alliance positioning find themselves in an uncomfortable gray zone, potentially facing restrictions from both blocs. Companies requiring neutral supply chain positioning to serve global markets discover that neutrality is no longer available in advanced semiconductors.

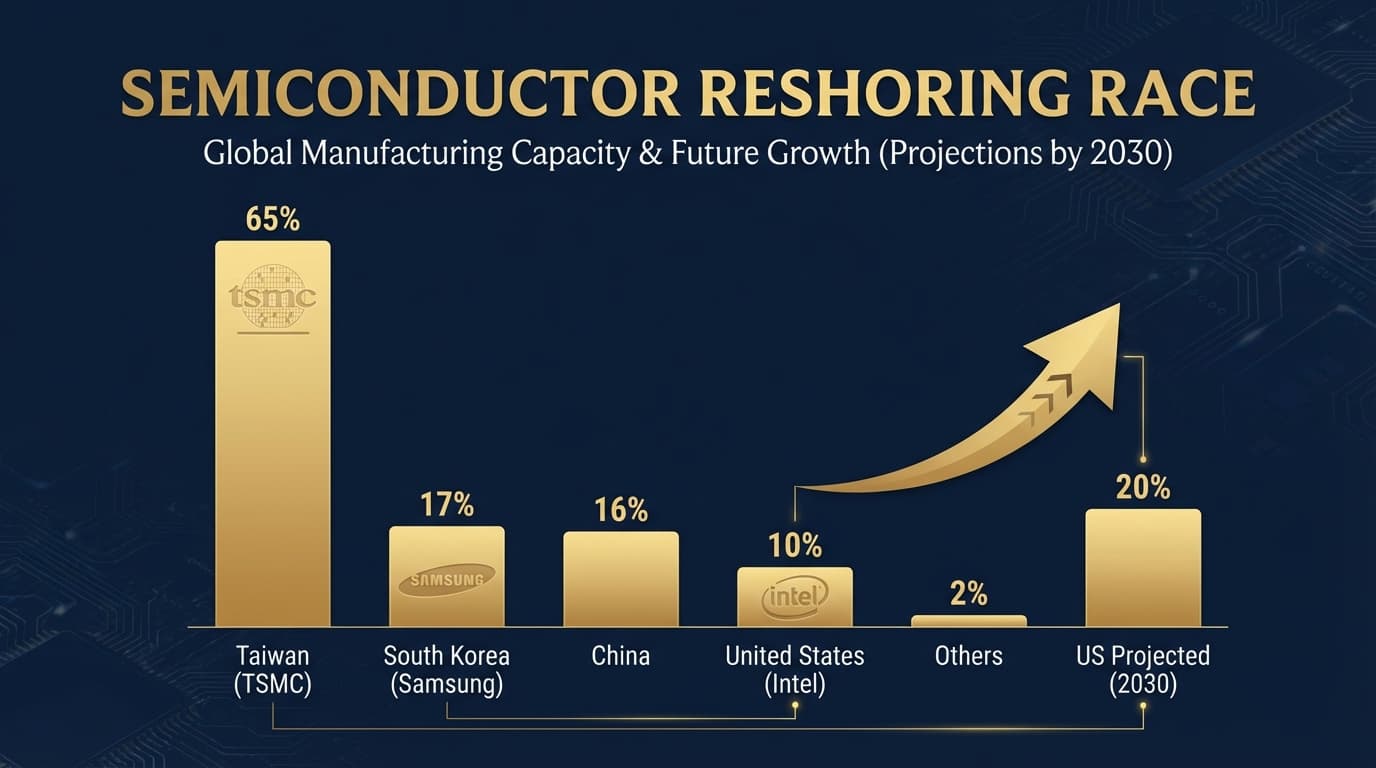

The Reshoring Catalyst

Taiwan's investment restrictions accelerate semiconductor reshoring to allied nations. If cutting-edge capacity cannot be accessed from Taiwan without alliance membership, the case for domestic fabs strengthens.

The numbers tell the story: Taiwan currently controls roughly 65% of global foundry capacity, with South Korea at 17% and China at 16%. The United States sits at just 10%, down from 37% in 1990. This concentration creates unacceptable vulnerability for advanced economies that depend on semiconductors for everything from military systems to automobiles. The policy response is massive: Intel, TSMC, and Samsung have announced over $200 billion in US fab investments, with government support through the CHIPS Act providing $52 billion in direct subsidies. By 2030, the US aims to reach 20% of advanced production, still far from self-sufficiency, but enough to mitigate catastrophic supply risk. This reinforces the subsidy dynamics examined in our Industrial Subsidies analysis.

Forecast 5: UK Sovereign Compute Requirements

55% probability: Between 2027-2029, the UK will require sovereign-compute certificates for any AI deployment in critical infrastructure (issued by the UK National Cyber Security Centre).

Critical systems (power, telecoms, etc.) could only use AI models running on certified sovereign hardware/cloud. It is a cyber-security measure turned trade barrier: by certifying only UK-controlled compute platforms, foreign AI providers would effectively be locked out of vital markets.

The Mechanism

The UK's National Cyber Security Centre already certifies security products. Extending this to AI compute infrastructure requires defining what constitutes sovereign control: ownership, data location, operational authority, and supply chain integrity.

For critical infrastructure operators, using non-certified AI systems would create liability exposure and potentially violate regulatory requirements. This effectively mandates domestic or allied AI infrastructure for the most valuable applications.

Investment Implications

UK sovereign compute requirements create a protected market for domestically-positioned players. UK cloud providers and data center operators gain guaranteed demand from critical infrastructure sectors that have no alternative to certified facilities. British AI startups with established government relationships become essential partners for foreign companies seeking market access, as their certification status enables compliance. Defense contractors expanding into AI infrastructure leverage their existing security clearances and government relationships to dominate the new sovereign compute market.

The challenged players face market access barriers that their global scale cannot overcome. US hyperscalers face restrictions that domestic regulation would never impose, as UK sovereignty requirements explicitly exclude foreign-controlled infrastructure regardless of technical capability. AI companies without UK-sovereign deployment options must either invest heavily in certified British facilities or accept exclusion from critical infrastructure applications. Critical infrastructure operators face significant compliance costs as they transition from global cloud services to sovereign alternatives with higher prices and potentially less capability.

The Allied Alignment Question

The key variable is whether UK sovereign requirements recognize allied infrastructure as equivalent to domestic facilities. A UK-only standard fragments the market maximally, requiring dedicated British infrastructure for all critical applications. A Five Eyes or NATO-aligned standard creates a larger but still restricted market, allowing US and allied cloud providers to compete for sovereign workloads. The choice signals broader UK positioning in the tech sovereignty competition and the degree to which it prioritizes national control over alliance efficiency.

Forecast 6: Japan EV Technical Standards

70% probability: By 2027, Japan will require all electric vehicles sold domestically to support Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) capability using Japanese technical standards, blocking Chinese EVs from its $40B market (per METI regulation).

Japan's energy security fears post-Fukushima drive this technical barrier. Mandating proprietary V2G standards serves dual purpose: energy resilience and market protection. Chinese EVs would need costly redesigns for compliance, effectively ceding market to Toyota/Nissan.

The Strategic Logic

V2G capability allows electric vehicles to feed power back into the grid during peak demand. For energy-insecure Japan, this creates a distributed energy storage network from its vehicle fleet.

By mandating Japanese-specific V2G standards, Japan achieves several strategic objectives simultaneously. Energy security improves through grid-integrated vehicles that can provide emergency power during outages or peak demand periods, particularly important for a nation traumatized by the Fukushima disaster. Market protection for domestic automakers occurs naturally, as Toyota, Nissan, and Honda can design for Japanese specifications from the outset while foreign competitors must adapt. Technology leadership in V2G systems creates export opportunities as other nations adopt Japanese standards. And exclusion of Chinese competitors occurs without the diplomatic friction of explicit tariffs, framed instead as technical requirements for grid stability.

Investment Implications

Japan's V2G standards create a protected domestic market for established Japanese automakers. Toyota, Nissan, and Honda benefit from both first-mover advantage in compliance and the cost disadvantage imposed on foreign competitors. Japanese battery and charging infrastructure companies become essential suppliers for the V2G ecosystem, with guaranteed domestic demand. Domestic EV component suppliers gain design-in advantages as automakers build vehicles specifically for Japanese specifications.

The challenged players face the classic standards fragmentation dilemma. BYD and other Chinese EV exporters must choose between expensive Japan-specific designs or accepting exclusion from a $40 billion market. Tesla faces additional compliance costs for V2G capability that its global platform was not designed to accommodate. Global EV platforms seeking unified designs discover that Japan requires a distinct model variant, eliminating economies of scale and adding complexity to product lines.

The Standards Fragmentation Pattern

Japan's approach illustrates how technical standards become trade barriers in practice. Each major market developing proprietary requirements fractures global EV development, forcing manufacturers to maintain separate designs for different regions. The compounding effect is severe: Japan mandates V2G, the EU requires specific battery passport requirements, China demands particular software standards, and the US imposes domestic content rules. Companies must either accept the cost of market-specific designs or choose which markets to abandon since there is no unified global EV product that satisfies all requirements.

The Emerging Tech Bloc Structure

These six forecasts reveal a consistent pattern: technology markets are fragmenting along geopolitical lines into distinct blocs with limited interoperability. Understanding this bloc structure is essential for any technology investment decision.

The Western Bloc

The Western bloc is led by the United States and includes the European Union, United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Australia. This bloc is characterized by shared export control frameworks that coordinate restrictions on technology flows to adversaries. Member nations increasingly recognize each other's security certifications, allowing products cleared in one market to access others without redundant approval processes. Coordinated restrictions on Chinese technology, from 5G equipment bans to semiconductor export controls, create a unified technology perimeter. Preferential market access within the bloc creates scale advantages for aligned companies while excluding competitors who cannot pass security scrutiny.

The Chinese Bloc

The Chinese bloc is centered on China and includes Russia along with aligned Belt and Road partners who depend on Chinese infrastructure investment and technology transfers. This bloc is defined by domestic standards designed to be incompatible with Western systems, forcing technology localization within Chinese-controlled ecosystems. Technology self-sufficiency has become the core strategic priority, with massive investment in indigenous alternatives to Western inputs. Alternative supply chains for critical inputs, from rare earth processing to chip manufacturing, reduce dependence on Western-controlled chokepoints. Export restrictions on strategic materials like gallium and germanium provide leverage in technology negotiations while protecting domestic advantages.

The Non-Aligned

A third category includes India, ASEAN nations, the Middle East, and others seeking to maintain access to both blocs. These nations pursue selective technology partnerships, choosing Western systems for some applications and Chinese alternatives for others based on cost, capability, and political considerations. Market-by-market regulatory arbitrage allows them to extract concessions from both sides competing for their allegiance. Their leverage comes from playing blocs against each other, threatening to adopt Chinese 5G if Western vendors don't offer competitive terms, for example. However, as bloc boundaries harden, the space for non-alignment shrinks, and these nations face increasing pressure to choose sides.

Investment Framework

Navigating tech sovereignty requires explicit assessment of geopolitical positioning alongside traditional investment criteria. Companies can no longer be evaluated purely on technology merit or market share; their bloc alignment and regulatory exposure now determine competitive viability.

Portfolio Considerations

Evaluating bloc exposure has become essential for any technology investment. Investors must understand what percentage of each company's revenue comes from each bloc, recognizing that cross-bloc revenue faces growing political risk. They must assess how market access restrictions would affect growth trajectories, particularly for companies dependent on Chinese market access. Supply chain dependencies on cross-bloc flows create vulnerability that may not appear in financial statements but can materialize suddenly when regulations change.

Assessing sovereign alignment requires understanding the political dimension of technology markets. Some companies benefit from state technology priorities, and those aligned with domestic champions or national security objectives receive preferential treatment. Others face explicit or implicit discrimination as foreign competitors. Understanding which regulatory approvals are required for key markets, and whether a company can realistically obtain them, has become essential due diligence. The defensibility of technology positions under fragmentation depends on whether the company's advantages translate across bloc boundaries or remain confined to specific markets.

Monitoring transition risks involves tracking the evolving regulatory landscape. Investors must understand the timeline for compliance with new standards and whether companies are positioned to meet deadlines. The cost of market-specific adaptation varies dramatically: some companies can modularize designs while others face fundamental architecture changes. Competitors better positioned for fragmented markets may gain share even with inferior technology if their bloc alignment provides market access advantages.

Sector Implications

The semiconductor sector divides most cleanly along bloc lines, with TSMC, Intel, and Samsung serving the Western bloc while SMIC and Huawei build Chinese alternatives. Non-aligned nations face difficult choices about which technology stack to adopt for their domestic infrastructure.

Cloud and AI services show similar bifurcation, with US hyperscalers dominant in the Western bloc and Alibaba and Tencent serving China. Regional players in non-aligned nations benefit from the opportunity to serve customers unwilling to choose either major bloc's technology.

IoT and hardware markets fragment along similar lines, with Apple and Western OEMs serving allied markets while Xiaomi and Chinese OEMs dominate in China. Non-aligned markets see intense competition as both blocs compete for allegiance.

The EV sector remains more contested, with Western OEMs and Tesla competing against BYD and Chinese brands across most markets. Standards fragmentation may eventually force similar bloc alignment, but for now all major players compete globally.

Conclusion: The Permanent Fragmentation

Technology sovereignty is not a temporary policy response. It reflects structural incentives that will persist for decades.

When AI capabilities determine economic and military advantage, no major power will accept dependence on rivals for critical inputs. When data flows carry surveillance and influence implications, governments will assert control over digital infrastructure. When technical standards determine market access, standards become instruments of economic competition.

The unified global technology market of 1990-2020 was an artifact of US hegemony and the absence of credible technological competitors. Both conditions have ended. The future is fragmented by design.

For investors, this means technology companies must be evaluated not just on product merit but on geopolitical positioning. Market access, supply chain resilience, and sovereign alignment now determine competitive viability as much as innovation and execution.

Series Navigation

Previous: Modern Mercantilism Overview

This analysis is part of our seven-part Modern Mercantilism research series: